(Note: for a detailed introduction to the Americal Division Veterans Association’s 2015 trip to Cebu, along with links to other stories from the trip, read our introductory story Cebu 2015: The Ghosts of World War II, 70 Years Later. Learn more about the World War II battle for Cebu here.)

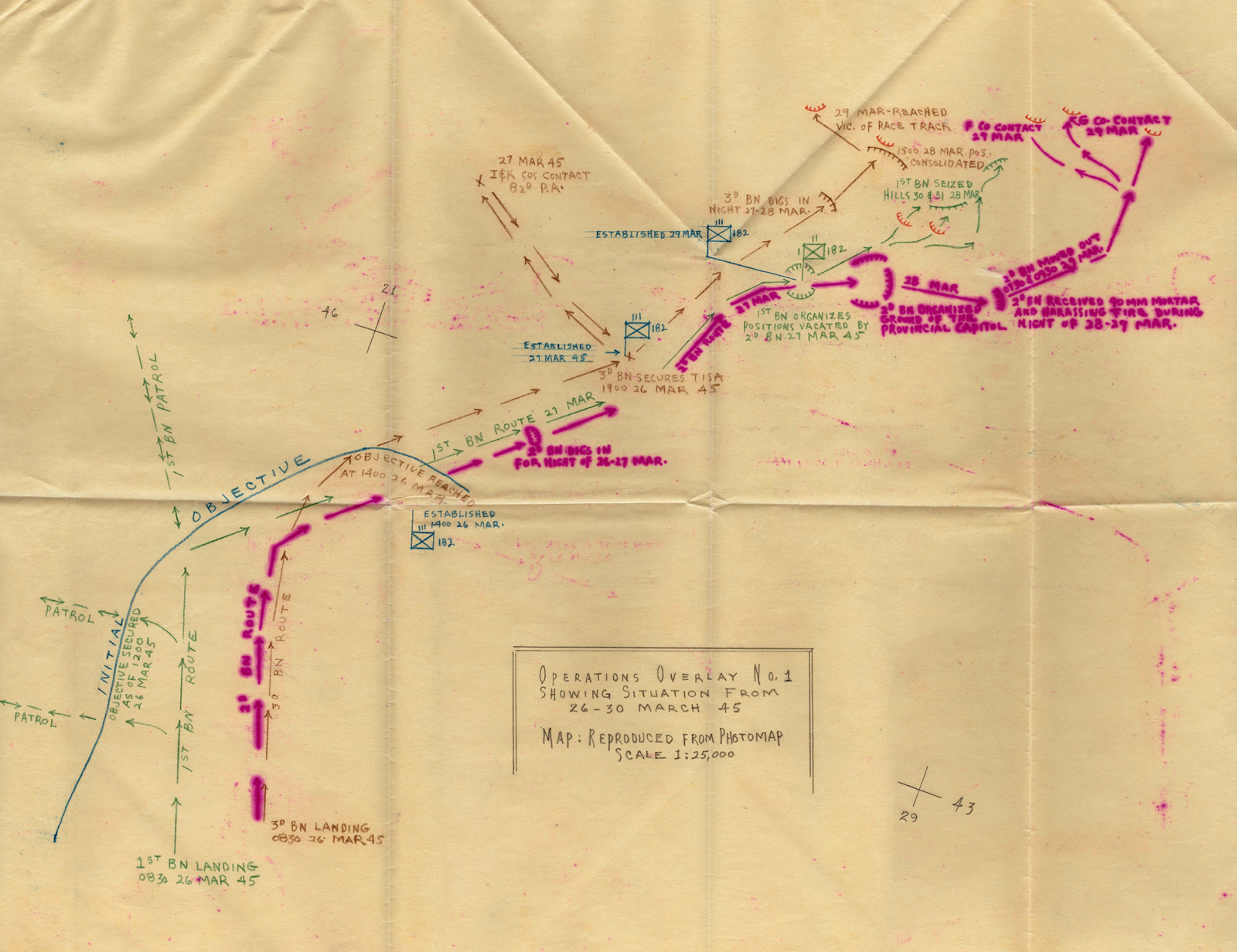

Following their successful landing at Talisay Beach in March 1945, the Americal Division advanced northwards along the coast of Cebu, towards the capital, Cebu City (see Photo #1). The Japanese occupied the city following their 1942 invasion of the island, and they ruled the local Filipinos with an iron fist for 3 years. Beginning in late 1944, carrier aircraft of the US Navy raided the island, and the capital city was heavily damaged. The pre-invasion naval and air bombardment only increased the damage (see Photo #2). Just one day after the invasion, troops of the Americal Division entered a ruined city, and had their first (and only) experience clearing an urban center.

In March 2015, I had the opportunity to tour numerous sites in Cebu City, along with Vietnam veterans from the Americal Division Veterans Association. We toured many of the sites where the men of the 182nd Infantry fought and died, and visited buildings and facilities where the Japanese committed atrocities against the people of Cebu. It was somewhat surreal to see many of these places – the scene of horrific crimes – still in use in daily activities. But when an entire city is subjected to brutal violence, the people of the city have no choice but to move on with their lives, carrying on in places where their ancestors had suffered terribly.

One of the first locations we visited was Museo Sugbo, a 19th century complex now serving as a museum to the long history of Cebu. During the first year of World War II, the American government used a series of small rooms to intern Japanese prisoners. Following the Japanese conquest of the island, they used these cells to imprison Filipino and American prisoners. In the upstairs of the main building, there is an entire room dedicated to World War II, with many fascinating artifacts from the war. It was at this point, on the first day of our touring, that I experienced my first emotional moments of the trip. Looking at a display of Japanese machine guns captured during the fighting in 1945, I wondered to myself if these guns had ever fired upon my grandfather Ed Monahan. I furthered pondered the fact that one of those guns, aimed just a little to the left or right, could have killed him – as well as me and my entire as yet unborn family (see Photo #3). It was a rather unsettling thought. My early morning emotional roller coaster continued as a listened to a young museum staff member tell us about other artifacts in the museum. She mentioned that her grandfather had been killed by the Japanese during the war. Her grandfather was killed by the Japanese on Cebu…my grandfather survived battles with the Japanese on Cebu. I realized that in a way, I was linked to this complete stranger.

That same morning we visited Cebu Normal University, a college focused primarily on teaching and nursing. On the morning of our visit, it was bustling with young students preparing for graduation. But in 1942, it was a Japanese military garrison, and headquarters of their secret police, the Kempeitai. We toured locations throughout the campus, many of which were the scene of terrible atrocities. Deep in the basement of one of the buildings, we visited classrooms – still in use today – where Cebuanos were tortured and raped by the Japanese (see Photo #4). Peaceful gardens and courtyards may still hold the remains of locals, executed during the war. I had never in my life visited a site of the war in the Pacific, and this first day brought the brutality into sharp focus for me.

At the end of our second day of touring, we had dinner in IT Park, a gleaming, modern center for technology professionals and home of corporate call centers. During World War II, this was the location of Lahug Airfield, one of the objectives captured by the 182nd Infantry during the first days on the island. This was the spot where John Mulcahy was shot through the side of the face, a wound he would recover from and return to the unit. A road (see Photo #5) now follows what was once the main airfield.

We visited other sites such as Rizal Memorial Library, headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army on Cebu, and University of the Phillipines, Cebu College, where announcements were made from a balcony to gathered Cebuanos by their occupiers. The last significant building we visited in the city was the Cebu Provincial Capital building (see Photo #6 and Photo #7). This grand structure was built during the American period of the early 20th century, and completed in 1938. It was damaged during the war, but was rebuilt and continues to function in its original capacity. This building was captured by the 182nd Infantry during the first days of the invasion, and Company G’s Fred Davis claimed to be the first soldier in the building.

The urban sites we visited over the course of the week really made me think. I’ve studied World War II since I can remember, but I had never visited any sites where the war had taken place. In many of these places in Cebu City, I pondered the absolute worst that war brings – the torture, rape, and murder of innocent civilians. And all of these sites were surrounded by the buzz of modern, daily life, bringing in to focus how the people of Cebu have healed from the war and moved forward with their lives.

Read the next piece in this series here: Cebu 2015, Part III: Bloody Battles in the Hills