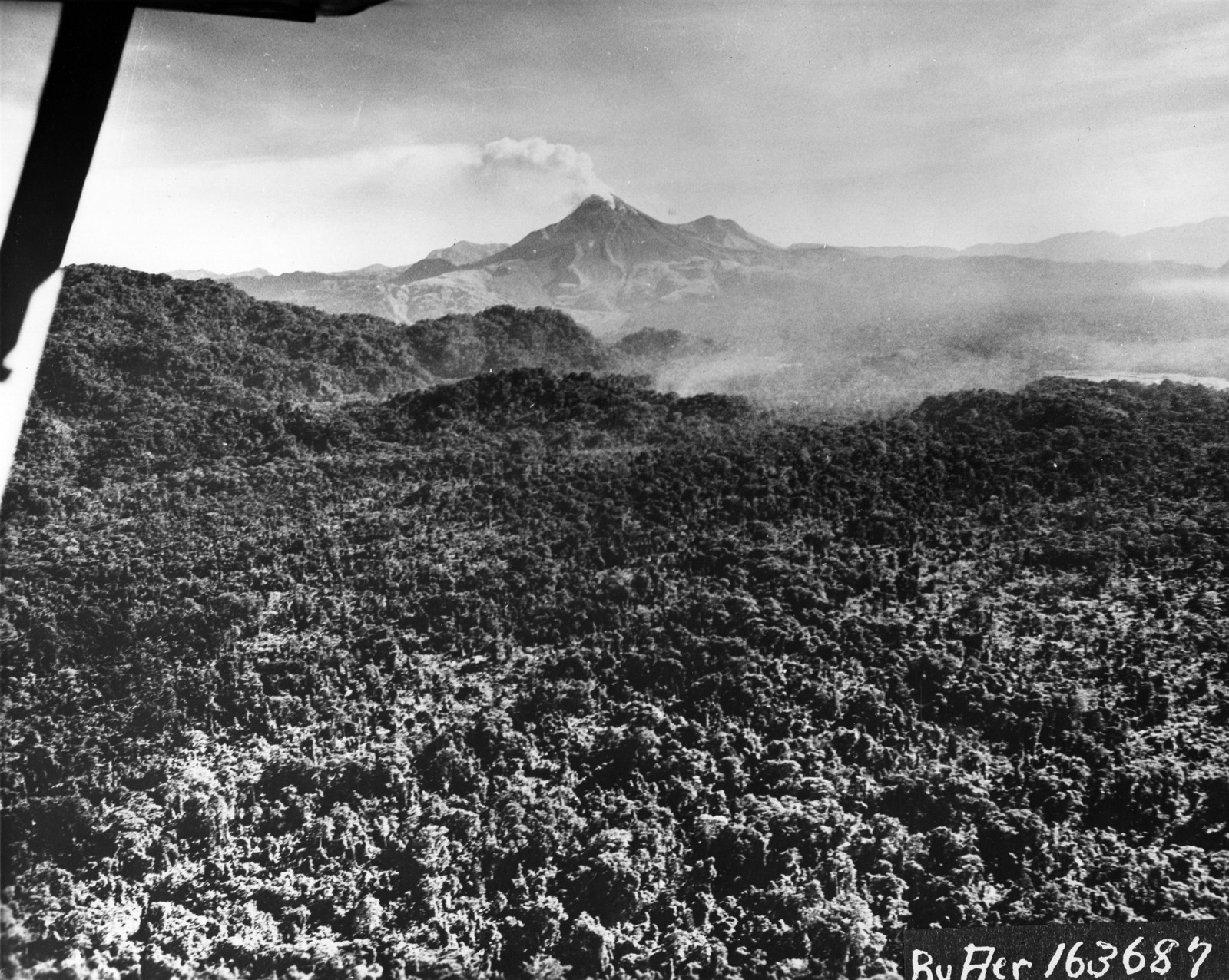

The ocean voyage from Fiji took more than a week, and on 28 December 1943, the convoy bearing the men of Company G arrived at Bougainville, and disembarked at Empress Augusta Bay (Google map view here). Allied forces had established a semi-circular perimeter in the jungle protecting three precious airfields. The Japanese forces on the island were entrenched further inland, but more importantly, were cut off from resupply and reinforcement by strong Allied naval and air presence. World War II was going badly for Japan by this point. The island of Bougainville itself was primitive, remote, and rugged – an easy place for the Japanese to hide. It was covered by dense jungle, as well as a number of volcanoes soaring as high as 10,000 feet, one of which can be seen in Photo #1. Earthquakes were a frequent occurence, as were torrential downpours. The jungle was thick, overgrown, and as Jack Morton recalled, “spooky.” The American mission on the island was to defend the perimeter around the airfields shown in Photo #2, and keep tabs on the Japanese through aggressive patrolling into the jungle.

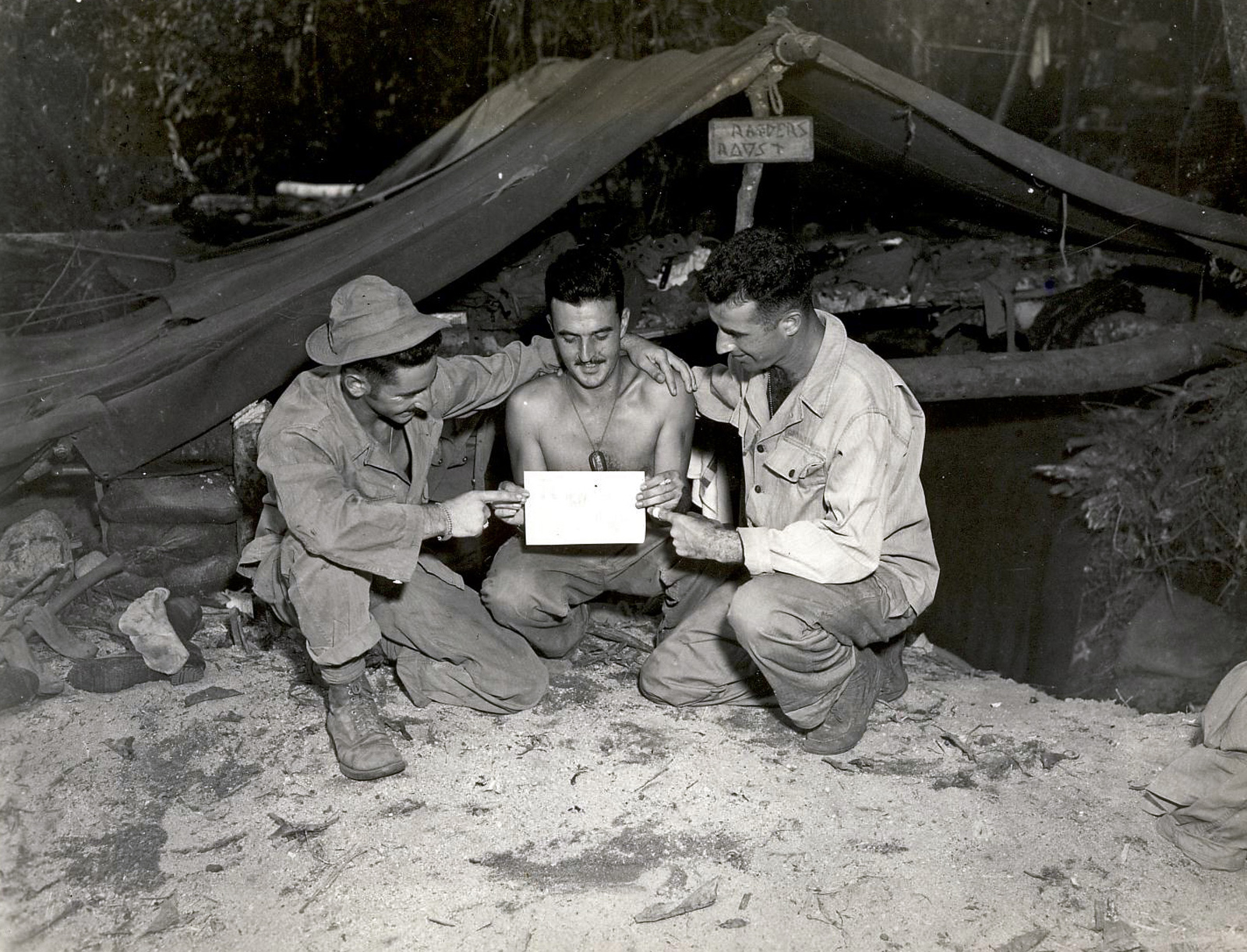

During their first few months on Bougainville, the men of Company G lived in a rugged, primitive campsite behind the lines. In Photo #3, Lieutenant Richard Roy (center) poses with Patrick Farino (left) and Howard “Inky” Simmons (right). Behind them is a typical home for the men during this period, with a platform and canvas roof hanging over a deep hole for shelter. This shelter was nicknamed “Raider’s Roost,” with a wooden carved sign hanging on the front. The men of Roy’s 2nd Platoon had given themselves the nickname “Roy’s Raiders.” This photo was taken in early February 1944.

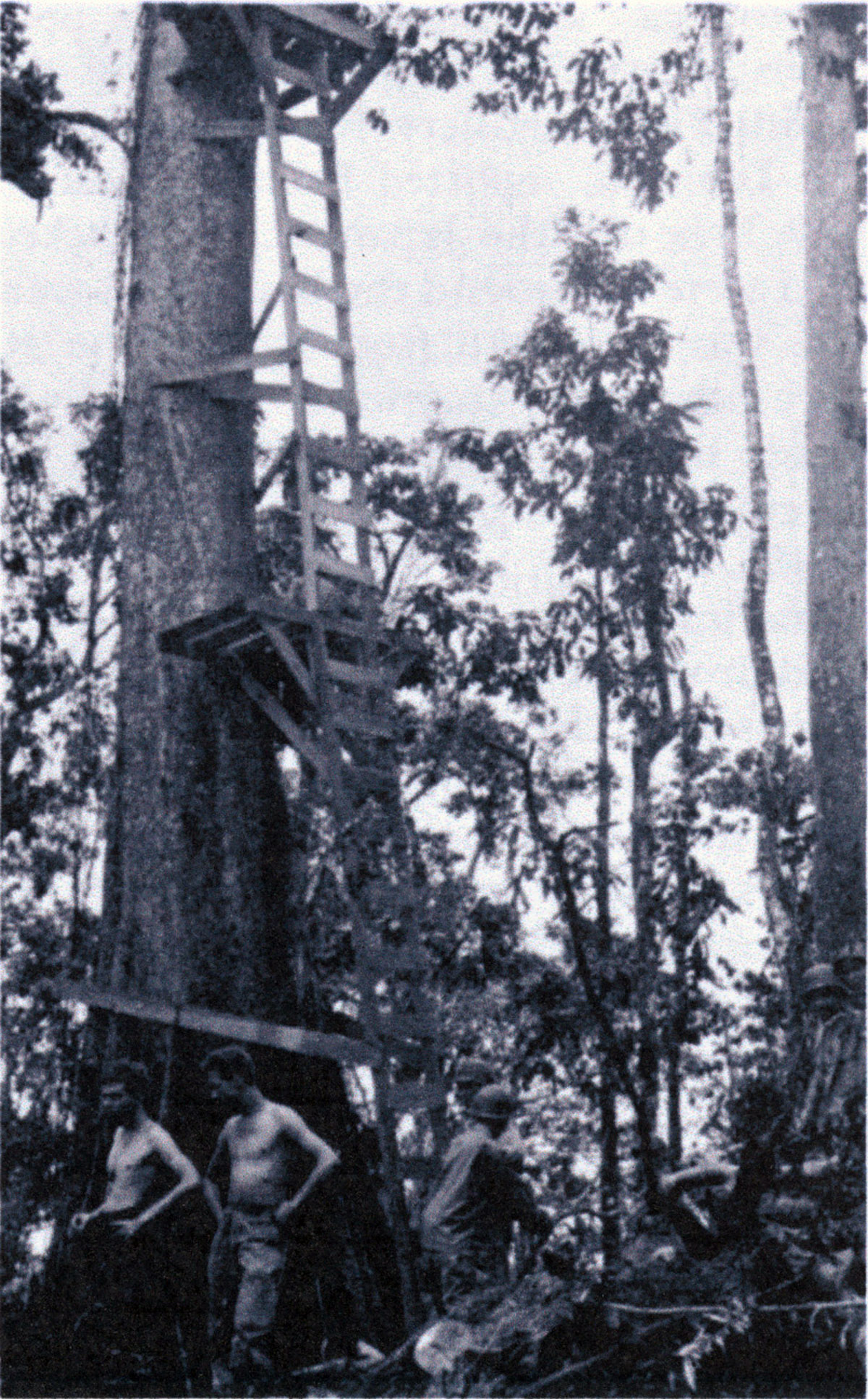

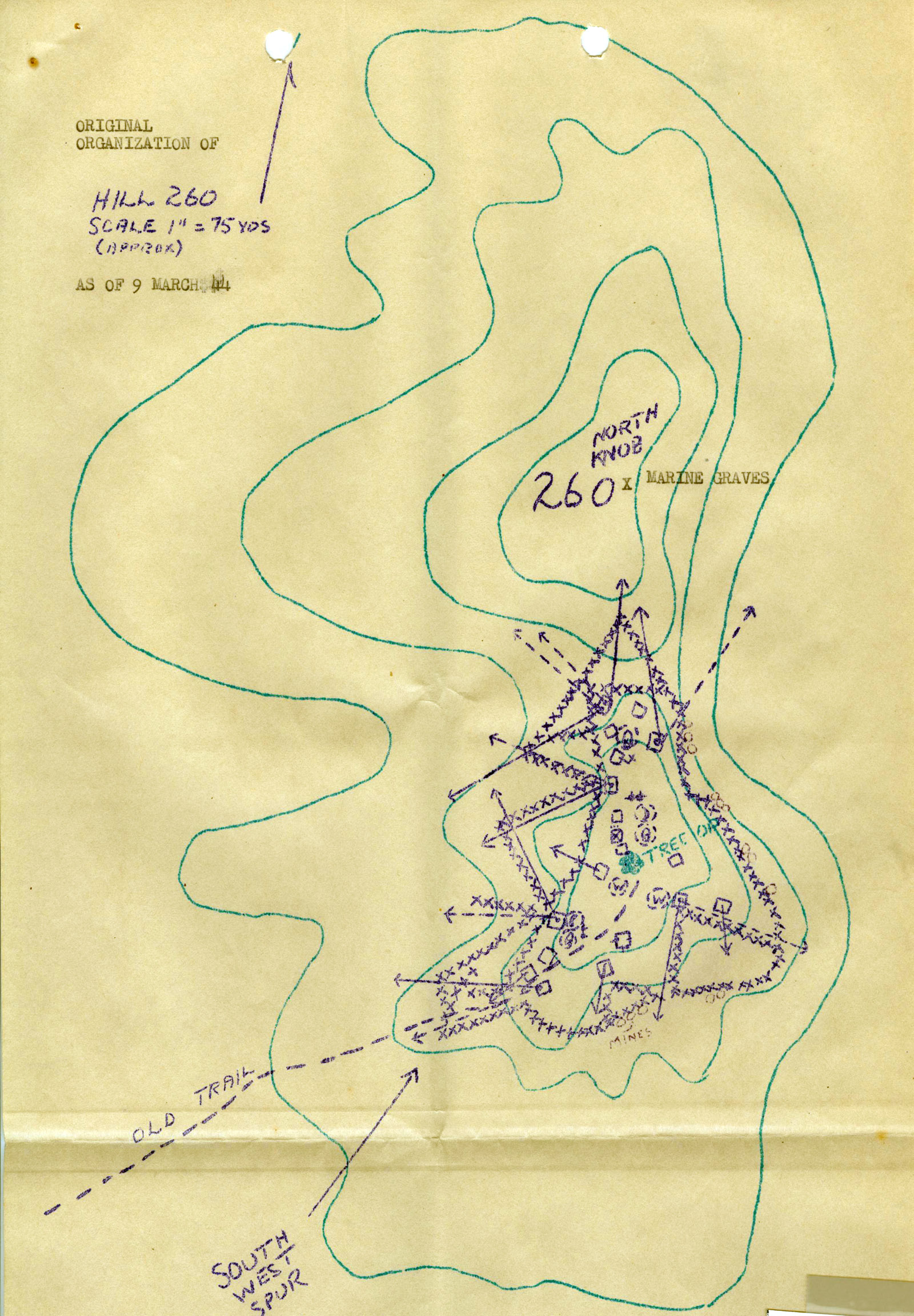

Throughout January and February, Americal patrols clashed with Japanese units in the jungles around the perimeter. Both sides sought to establish new positions, particularly in areas which afforded good observation of their adversary. American forces set up an observation post on the top of Hill 260, just outside the American lines, along the Torokina River. An observation platform was built atop a huge Banyan tree. From this small wooden treehouse 125 feet in the air, observers could take in the jungle for miles around. Photo #4, taken in early 1944, shows the base of that observation post, with a wooden ladder leading high up into the Banyan tree. A platform above housed bunks, telescopes, and radios. Hill 260 was in the 182nd Infantry sector of defense, yet it lay out beyond the main perimeter, sticking out like a sore thumb in a hostile jungle. The hilltop was shaped like an hourglass, with the Observation Post Tree (OP Tree) on the South Knob of the hill. The map in Photo #5 shows the defensive positions on top of the hill as of 9 March 1944.

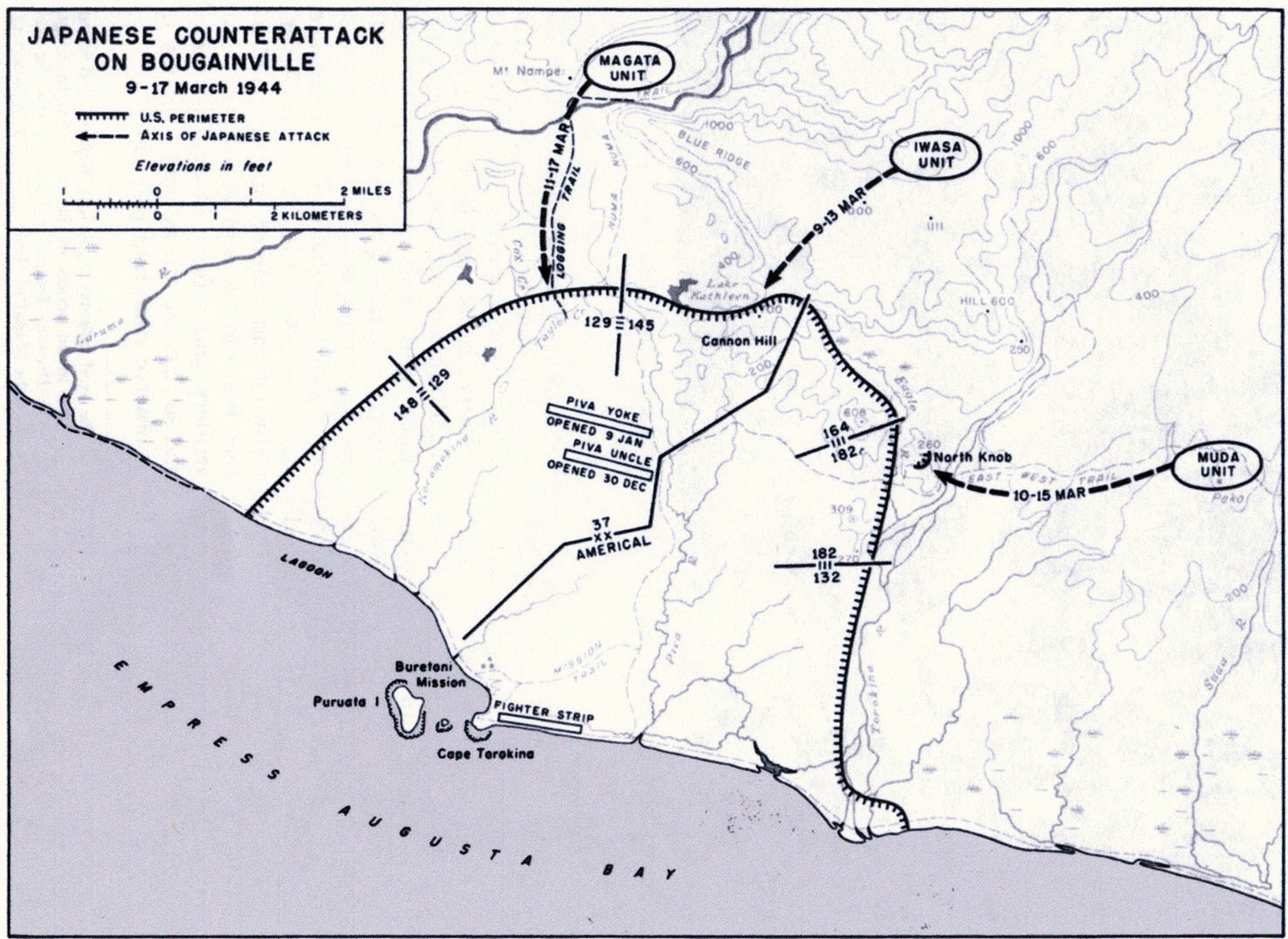

Japanese forces on Bougainville were still strong and organized in the first months of 1944. In March, they launched a massive counterattack against the American perimeter. The battle began with a massive artillery bombardment of the entire American sector on the morning of 8 March.Their objective was to drive the American forces back into the sea, and retake the airfields. But despite the heaviest concentration of artillery support that the Japanese would mount during the entire Solomons campaign, the offensive was doomed. Japanese intelligence estimates greatly underestimated the size of American forces on the island. Allied artillery and airpower struck back to essentially silence the Japanese artillery barrage. The battle began in earnest the following day, and over the course of the next week, three separate Japanese assault groups threw themselves against the semicircular defensive line, as seen in Photo #6.

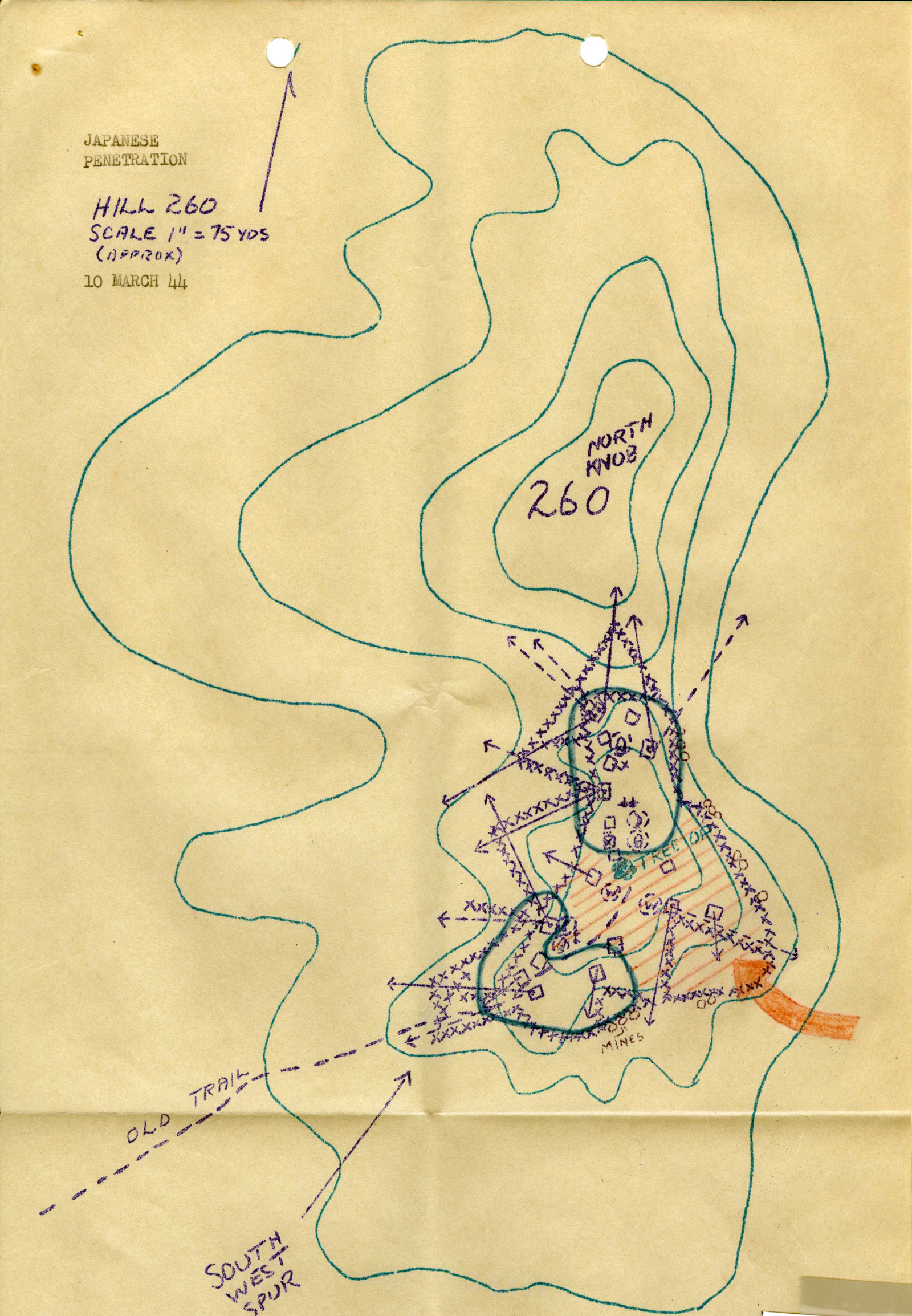

The Japanese offensive, while outnumbered on the whole, directed massive force at key positions in overwhelming numbers. The initial assault on Hill 260, still outside the main American perimeter, consisted of perhaps 1300 Japanese soldiers of the “Muda” group. The defenders on top of the hill, composed primarily of men from the 182nd’s Company G, had only 78 men to hold back the assault. They were quickly overwhelmed. The Japanese advanced up the southeast corner of the hill, throwing themselves across barbed wire when necessary. They quickly took the area around the OP Tree, while small forces of survivors from the original garrison held on desperately. The map in Photo #7 shows the penetration of Japanese forces in red.

The orders from on high to the American forces on the hill were clear: “Hold at all costs.”Adhering to the orders to hold, officers of the 182nd threw wave after wave of attacks at the Japanese positions on Hill 260. Occasional success was met with Japanese counterattack. The fighting went on for days. This report, signed by Lieutenant Colonel Dexter Lowry, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, recounts the first two days of the battle in excruciating detail. Men from Company G were lost in the initial Japanese attack, and still more were lost in a failed American counterattack on the hill on 11 March. Numerous men from Company G were awarded medals for bravery during this 11 March attack and subsequent retreat.

As the battle settled into a routine of American counterattack and retreat, artillery support from behind the lines began to take a toll on the Japanese entrenched on top of the hill. Over the course of the battle, perhaps 10,000 rounds of artillery and mortar fire were dropped on the South Knob of the hill. In Photo #8, a 155mm howitzer of the 155th Sea Coast Defense fires a round on Bougainville during the Japanese attack. The insistence on head-on thrusts up the hill began to take a terrible toll on American units. In Photo #9, taken on 15 March 1944, a soldier on the ground buries his head in his hands, weeping over a friend killed on Hill 260.

By the second week of the battle for Hill 260, the Japanese forces atop the hill were mostly isolated, but still firmly entrenched. The Americans had retaken the North Knob of the hill, and established a perimeter around the base of the hill. Photo #10, taken on 19 March, shows the crest of Hill 260 through a dense growth of trees. Artillery fire can be seen exploding on top of the hill. In the foreground are barbed wire fencing and discarded supplies. American units tried innovative methods to dislodge the Japanese. They rigged gas pipelines and improvised gasoline can launchers to try to burn the Japanese out, to no avail. Eventually, artillery and even anti-aircraft pieces were lugged into the jungle and mounted in positions that enabled them to fire almost point blank at the Japanese. In Photo #11, a 75mm cannon mounted on a nearby hill blasts away at Hill 260.

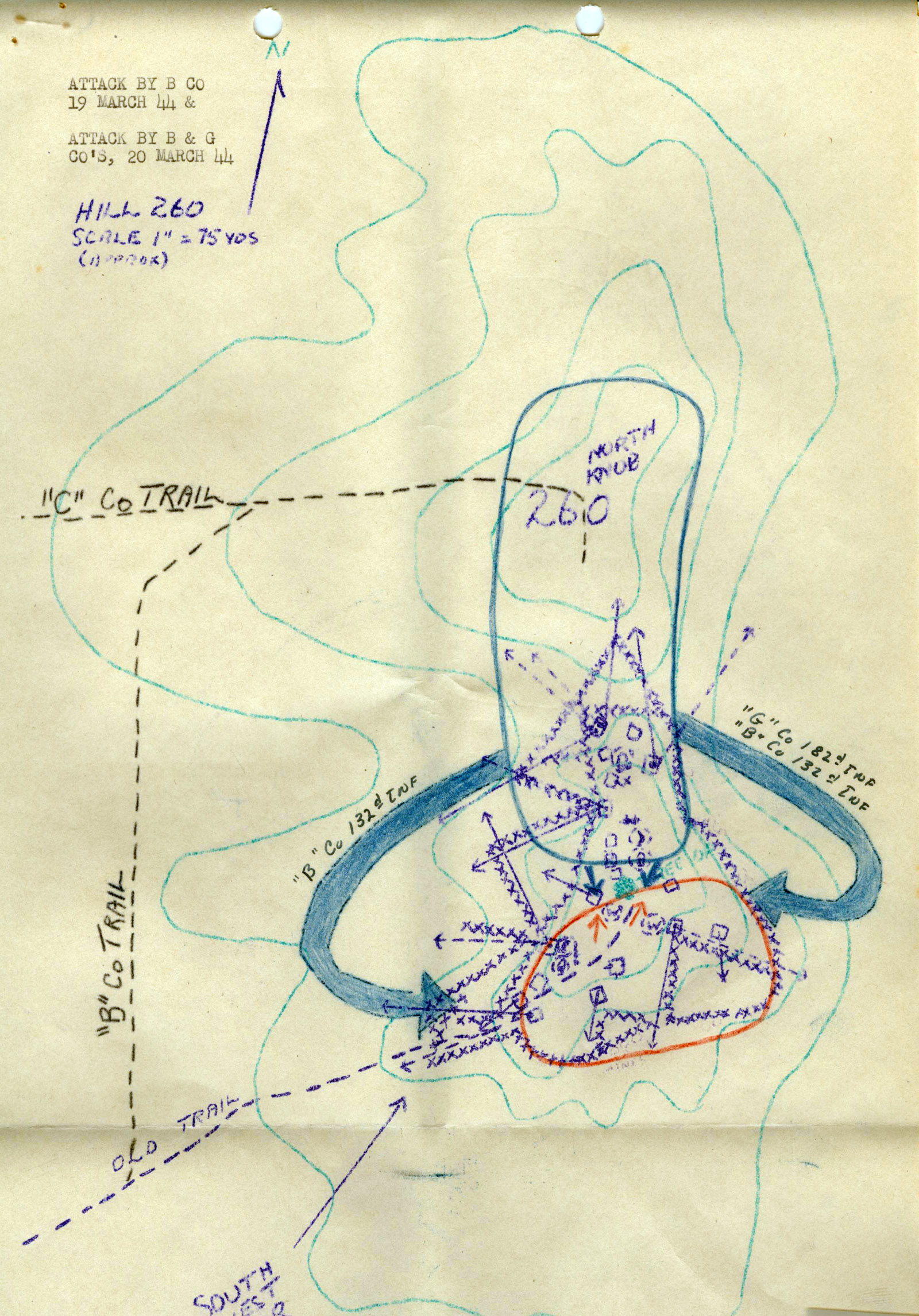

Infantry units continued to launch all-out attacks on the Japanese forces on the South Knob. The map in Photo #12 shows two separate attacks, one on 19 March (left), and one on 20 March (right). Both attacks moved from safe positions on the North Knob, down into the jungle, and then up the side of the South Knob. Company G advanced on 20 March with Company B of the 132nd Infantry. They fought their way to the top of the hill, suffering a number of casualties. At the top, they observed Japanese units signaling their surrender. As the Americans advanced to investigate, the Japanese dropped back in their hole, and mortar fire began to rain down on the Americans. It had been a trap. News of the fake surrender was reported in American newspapers, complete with an account from Lieutenant Richard Roy. Eddie McCarthy of Company G was killed during this assault, and Ed Monahan was among those wounded.

On 28 March, American forces advanced up the hill and discovered that the few remaining Japanese soldiers had abandoned the hill and disappeared back into the jungle. The Hill was at last back in American hands. Men scurried about preparing new defensive positions. In Photo #13, the toll of the American artillery fire over the previous three weeks is evident. Looking south from the North Knob, the blasted remnants of what was once a thick jungle were all that remained. The hill was in ruins when the Americans re-occupied it. 21 American bodies were recovered in the rubble, along with over 200 Japanese corpses. In Photo #14, an American soldier dumps lime on a Japanese corpse atop the hill. In Photo #15, a soldier burns refuse with a flamethrower. The Banyan tree, home of the precious Observation Post, and the key objective of the battle, lay in ruins after the fighting, as seen in Photo #16. Photo #17 shows Japanese weapons collected in the cleanup on Hill 260.

The cost of victory had been high. On 9 March, the day before the attack, Company G reported 147 men on duty. The day after the fighting concluded, 29 March, Company G could muster only 85 men. The rest had been killed, wounded, or had fallen ill. During the fighting, the 182nd Infantry underwent a dramatic change of command. In a period of less than a week, numerous men in positions of importance were reassigned. Colonel William Long, commanding officer of the 182nd Infantry Regiment, and Lieutenant Colonel Dexter Lowry, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion of the 182nd, were both reassigned. Their replacements, Lieutenant Colonel Floyd Dunn (left, new CO of 182nd) and Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Sauer (right, new CO of 2nd Battalion) pose in Photo #18 at the tattered remains of the OP Tree after the conclusion of the battle. Company G was not immune to these sweeping changes. Company CO Captain Donald Pray was reassigned, as was First Sergeant Frank Fitzgerald. Veterans of the unit continued to argue for decades about what could have been done to avoid the initial loss of the hill, and the protracted battle and heavy casualties that followed.

The defeat of the Japanese at Hill 260, and everywhere else along the American perimeter of the March offensive, proved the end of significant organized Japanese resistance in the Solomon Islands. Their losses were so great that they would never again prove to be an offensive threat on Bougainville. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 500 Japanese soldiers died in the fighting on Hill 260 alone, and many more were wounded. As many as 5000 may have perished in the larger offensive, against only 264 Americans killed.

Next Chapter: Bougainville: The Fight Continues